Busting the "Myth Busters": Untruths About Abortion and Mental Illness Forced on Schools

March 20, 2019

Teachers and staff who work at secondary schools in England are being given a fact sheet that purports to correct a number of myths about abortion. One of these "myths" is on abortion and mental illness:

"Successive studies and research reviews have demonstrated that the experience of abortion makes little or no difference to women’s mental health," the fact sheet claims. "Research includes an extensive systematic review of research evidence, conducted by the Academy of Royal Medical Colleges in 2011 and referenced by NHS Choices."

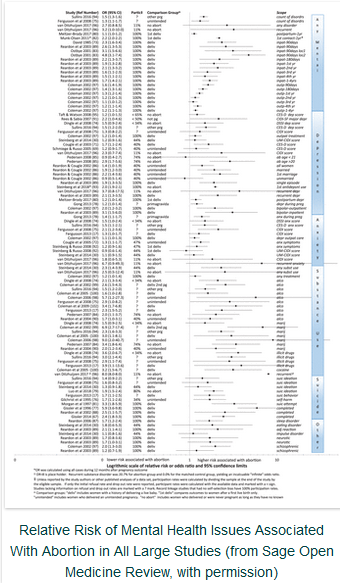

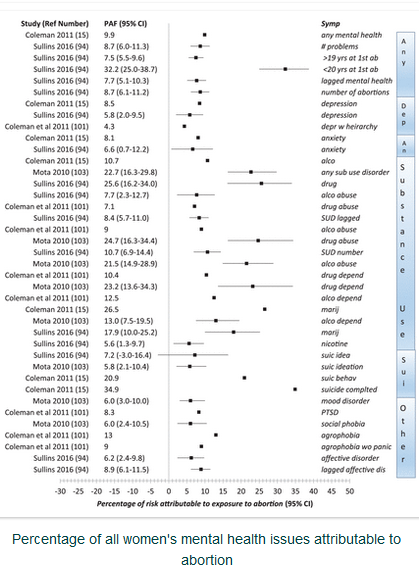

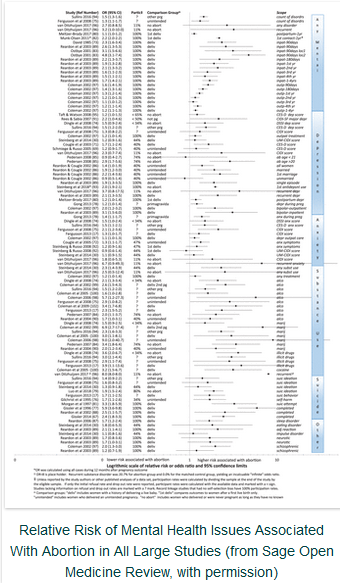

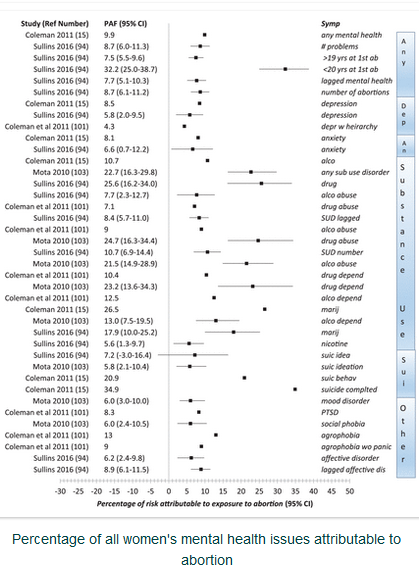

Yet this "myth busting" itself needs some debunking. Both pro-choice and pro-life researchers actually agree that abortion contributes to mental health problems, at least for some women, according to a comprehensive review of more than 200 medical studies on abortion and mental health.

There is no disagreement over the fact that abortion may trigger, worsen, or exacerbate mental health problems, but rather the main controversy is over whether abortion is ever the sole cause of severe mental illnesses, according to David Reardon, director of the Elliot Institute and author of the review published in Sage Open Medicine. Additional conflicts arise over how known facts are best interpreted and over the definition of key terms.

The review of abortion and mental health (AMH) issues identifies twelve findings around which researchers on both sides of the debate agree. These include:

- Abortion contributes to mental health problems in some women.

- There is insufficient evidence to prove that abortion is the sole cause of the higher rates of mental illness associated with abortion.

- The majority of women do not have mental illness following abortion.

- A significant minority of women do have mental illness following abortion.

- There is substantial evidence that abortion contributes to the onset, intensity, and/or duration of mental illness.

- There is a dose effect, wherein exposure to multiple abortions is associated with higher rates of mental health problems.

- There is no evidence that abortion can resolve or improve mental health.

- Risk factors exist that identify women at higher risk.

- A history of abortion can be used to identify women at higher risk of mental health issues who may benefit from referrals for additional counseling.

- No single study design can adequately address and control for and address all the complex issues that may be related to the AMH issues.

Beyond these points of consensus, there is ongoing controversy over the definition of terms, differences in emphasis, and political objectives between what Reardon describes as AMH proponents and AMH minimalists. AMH proponents tend to interpret the data in ways that emphasize the need for better screening and counseling of women seeking abortions, whereas AMH minimalists generally oppose any change in abortion services as an unnecessary burden on women's "right to choose."

Evidence From “Both Sides” Shows Abortion Risks

Notably, while many pro-choice activists dismiss the idea of any link between abortion and mental health issues, this denial of any and all links is supported by AMH minimalists whose own research has confirmed higher rates of mental illness following abortion for some women.

For example, even the hand-picked team of abortion-supporting psychologists who wrote the 2008 Report of the American Psychological Association Task Force on Mental Health and Abortion, acknowledged that “it is clear that some women do experience sadness, grief, and feelings of loss following termination of a pregnancy, and some experience clinically significant disorders, including depression and anxiety.”

Indeed, the APA Task Force went further, identifying at least 15 risk factors which can be used to identify the women who are at greater risk of psychological problems after an abortion:

- “terminating a pregnancy that is wanted or meaningful”

- “perceived pressure from others to terminate a pregnancy”

- “perceived opposition to the abortion from partners, family, and/or friends”

- “lack of perceived social support from others”

- “low self-esteem”

- “a pessimistic outlook”

- “low perceived control”

- “a history of mental health problems prior to the pregnancy”

- “feelings of stigma”

- “perceived need for secrecy”

- “exposure to antiabortion picketing”

- “use of avoidance and denial coping strategies”

- “feelings of commitment to the pregnancy”

- “ambivalence about the abortion decision”

- “low perceived ability to cope with the abortion prior to the abortion”

Reardon said that these conclusions by the pro-choice APA Task Force demonstrate that AMH minimalists agree with AMH proponents regarding the existence of such risk factors which predict and explain why some women do experience significant emotional and mental health issues following abortion.

For example, experts on both sides would agree that a woman feeling pressured by her partner into an unwanted abortion, in violation of her maternal desires and moral beliefs, faces a much higher risk of suffering subsequent emotional problems related to her abortion experience.

“Among those doing the actual research, there is no longer any doubt regarding the fact that a history of abortion is predictive of more mental health problems,” Reardon said. “The real controversy is over whether or not abortion's contribution to mental health problems is significant enough to require abortion providers to discourage abortion among the groups of women at greatest risk of negative outcomes."

Research Barriers Hinder Further Agreements

While Reardon's review identified numerous areas of agreement between AMH proponents and minimalists, over two-thirds of his review is devoted to exploring the areas of disagreement and the barriers that hamper the research.

Regarding research efforts, since it is unethical and impossible to randomly assign women to have abortions, it is simply not possible to design studies that can gather enough data to control for complex factors that may influence how a woman responds to an abortion.

Typically, less than half of abortion patients are willing to participate in follow-up studies. Moreover, it is also known that the women who feel most stressed about participating in follow-up studies are also most likely have negative feelings. The result is that the samples of women who are surveyed are not representative of the whole population.

In addition, it is nearly impossible to investigate every facet of women's lives before and after an abortion that may contribute to the ways it effects their lives.

“An abortion does not occur in isolation from interrelated personal, familial, and social conditions that influence the experience of becoming pregnant, the reaction to discovery of the pregnancy, and the abortion decision,” Reardon wrote. “These factors will also effect women’s post-abortion adjustments, including adjusting to the memory of the abortion itself, potential changes in relationships associated with the abortion, and whether this experience can be shared or must be kept secret. These are all parts of the abortion experience.”

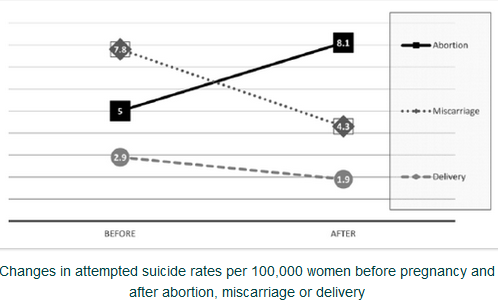

This complex nest of experiences means that researchers need to consider the “entirety of the abortion experience,” including the women’s experiences in the time both before and after abortion and not just on the day itself.

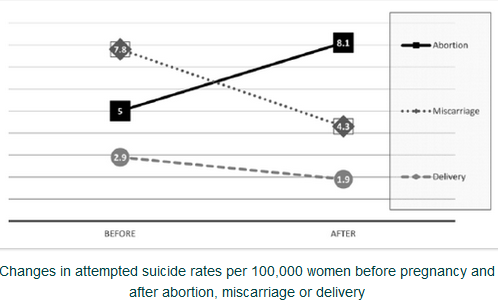

Moreover, most women experience positive and negative emotions. Relief that the abortion is over may be mingled with feelings of hope, loss, guilt, anger, and a host of other emotions. Even this mix of emotions may be ever changing. Conflicting emotions may change in intensity over time, or suddenly appear after years of calm. Many women may develop defense mechanisms to keep negative emotions at bay, but subsequent events, such as a later pregnancy or the death of a loved one, may trigger long-dormant emotions related to the abortion.

These are just a few of the factors that make it difficult to measure the effects of abortion. The difficulty in gathering sufficiently complete data makes it impossible to reliably identify how many women have negative outcomes, to what degree abortion itself contributed to their problems, or any other definitive conclusions.

Poorly Defined Terms Confuse Rather Than Clarify

In addition, many studies on abortion revolve around poorly-defined terms. Reardon wrote that "the resulting lack of precision and nuance" in measuring and describing variations among women's responses "contributes to AMH minimalists and AMH proponents talking past each other and contributes to overgeneralizations regarding research findings, especially in the press releases and position papers of pro-choice and anti-abortion activists.”

For example, many researchers assume that abortions are the result of "unwanted" pregnancies and use this term in their work. However, research has found that many women who have abortions either initially planned or wanted to be pregnant, were welcoming or open to the idea of having a child, or would have preferred to carry to term. The failure to distinguish between these many variations of women's actual experiences has led to many inaccurate overgeneralizations.

Another issue, Reardon said, is the ambiguity around the term “relief.” While abortion advocates frequently point to studies finding that most women report feelings of relief after abortion as evidence that they feel positively about their abortions, the sources of such relief are not defined. Further, relief is only one of many reactions, both positive and negative, that women report after abortion – and the predefined lists of emotions used in such studies often limit women to a handful of choices that don't represent the full range of their experiences.

Indeed, Reardon said that the frequently-made claim that relief is "the most common reaction to abortion" is misleading because "it falsely suggests that a truly representative sample of all women having abortions have been queried about their most prominent and common reactions." In fact, all of the studies addressing relief have dropout rates of 50 percent or higher. This problem is exacerbated if those tend to anticipate or experience more positive reactions while those who drop out tend to anticipate or experience more negative reactions.

Further, researchers often report relief as a single category while grouping together or "averaging" multiple negative emotions into a single score, thus diluting the number of negative emotions reported. Also, in one of the most frequently cited studies in which women reported feeling relieved after abortion, "the same researchers also found that between the three month and two year post-abortion assessments, both relief scores and positive emotions decreased significantly while the average for negative emotions increased." Subsequently, however, headlines in the media claimed that the study found the vast majority of women were satisfied with their abortion.

"Similar questions, posed to a different self-selected sample of women seeking post-abortion counseling, reveal that 98 percent of that sample of women regret their abortions," Reardon wrote. "It is important to recognize that neither of the two samples just cited represent the general population of women having abortions. Given the fact that so many women refuse to respond to questionnaires about their abortions, it is impossible to ever be certain what 'the majority' of women feel or think about their past abortions at any given time, much less through their entire lifetimes."

When Ideology Trumps ScienceReardon believes that the evidence of problems found across a realm of studies points to an ideological basis for the controversy over abortion and mental health.

"Given the weight of the many statistically validated studies cited above, much less the reports of clinicians and women who attribute PTSD symptoms to their abortions, it seems evident that the effort of a few AMH minimalists to categorically deny that abortion can contribute to traumatic reactions is driven by ideological considerations, not science," he wrote.

"That said, it should also be noted that not all women will experience abortion as traumatic. Moreover, the susceptibility of individuals to experience PTSD symptoms can also vary based on many other pre-existing factors, including biological differences. So the risk of individual women will vary, as it does for every type of psychological reaction."

Still, he wrote, "the evidence is clear: some women do experience abortion as a trauma. The prevalence rates and preexisting risk factors may continue to be disputed, but the fact that abortion contributes to PTSD symptoms in at least a small number of women is a settled issue."

Possibilities for Both Sides to Collaborate On Better ResearchEven given the inherent difficulties of the research and ideological biases surrounding the AMH controversy, Reardon offered some suggestions for moving forward and conducting better research.

First, he recommends having teams of researchers with mixed views on abortion cooperating in the design, analysis, and interpretation of results. Second, he recommends that such mixed teams should participate in the design of a national longitudinal prospective study that would track a sample of women over many years, before they are exposed to their first pregnancies, so the women who have abortions can be compared to other women.

He also called for "better adherence to data sharing and re-analysis standards," noting that a number of prominent pro-choice research psychologists have refused to share their data for verification and reanalysis by other researchers. This lack of cooperation is actually in violation of the American Psychological Association's own ethics rules, which require psychologists to provide data from their studies for reanalysis by others.

"All of these steps will help to provide health care workers with more accurate information for screening, risk-benefits assessments, and for offering better care and information to women both before and after abortion and other reproductive events," he concluded.

Reardon's complete review is

available online, free of charge from Sage Open Medicine.

# # #

Citing: The Abortion and Mental Health Controversy: A Comprehensive Literature Review of Common Ground Agreements, Disagreements, Actionable Recommendations, and Research Opportunities. Reardon DC. Sage Open Medicine. Vol 6:1-38, 2018.

Online link to original news release here.

Please Forward this Email to Your Friends and Associates.

But if you do forward it, you should remove the unsubscribe link at the bottom or they may unsubscribe YOU by mistake.